By Elizabeth Peters

Olman picked up this book while we were in the Maritimes this summer and highly recommended it to me, saying I’d really like the heroine, Amelia Peabody - “a feisty and headstrong Victorian woman, who embodies all the values of the British Empire, but is somewhat restricted by doing so in a female form” - as well as the friendship that develops between Peabody and a younger woman (no, there is no lezzing out á la Fingersmith). Just don’t expect it to be a satisfying mystery.

Olman was right. I did enjoy Crocodile on the Sandbank very much. The beginning was awesome, as it sets up the adventure in which Amelia Peabody is about to begin. What else is an unconventional Victorian woman to do when she inherits a modest fortune and has no wish to marry? She embarks on an exotic voyage, of course! Almost immediately, she rescues, adopts and befriends an abandoned, fallen young woman named Evelyn, who becomes her travelling companion. You can’t help but admire this female protagonist, who proclaims:

I may say, without undue egotism, that when I make up my mind to do something, it is done quickly. The lethargic old city of the Popes fairly quaked under my ruthless hand during the following week.”

For once, I am of complete accord with Olman on both the strengths and weaknesses of Crocodile on the Sandback - it had a great premise that got undermined by the narrative. I also agree with Olman that there wasn’t much of a mystery, and that the so-called mystery was actually in service of the narrative, which is more of action-adventure than a mystery (which I guessed early on anyway, so it must have been pretty obvious!).

[SPOILER ALERT]

Even more so than Olman, I was terribly disappointed with the ending when Amelia got married and had a child. Don’t get me wrong, as I quite enjoyed the sexual tension between her and Emerson. But what made Peabody so appealing for me was her fierce independence and unconventionality. She was proud being a thirty-two year old spinster, and makes a point of explaining her opinions about marriage to Evelyn:

…my nature does not lend itself to the meekness required of a wife in our society. I could not endure a man who would let himself be ruled by me, and I would not endure a man who tried to rule me.

As a result, I wasn’t expecting Peabody to settle down so soon, and was hoping that her romance with Emerson would continue for at least a few more books, so that readers could enjoy her as Amelia Peabody (not Emerson), not beholden to any man, or any prosaic duties of domesticity. So I'm in no dire need to read the next book. But like Olman, I wouldn’t say no if someone were to lend me the next Peabody book.

Addendum: after perusing the wikipedia, it seems that Peters had originally thought this was a one-off, and I think the book was so popular that a series was born. Peters had rued the fact that in Crocodile, she had stated Peabody's age, and would've probably made her a few years younger had she been planning a whole series. So that was interesting to know.

It's been several years and I managed to crack 40 one time, but have yet to read 50 books in a year...

Friday, December 23, 2011

Tuesday, December 13, 2011

Book 40 - The G.N.B. Double C

The Great Northern Brotherhood of Canadian Cartoonists

A Story from the sketchbook of the cartoonist “Seth”

This is my first time reading a comic by Seth. Being already familiar with the work of Joe Matt and Chester Brown, I knew a little bit about the friendship and history (as well as the idiosyncracies) of this trio. A mutual friend recently lent Conan and I a bunch of comics (City of Glass, The Death Ray), which helped boost my book quota. The G.N.B. Double C comes in at an auspicious Number 40.

This is my first time reading a comic by Seth. Being already familiar with the work of Joe Matt and Chester Brown, I knew a little bit about the friendship and history (as well as the idiosyncracies) of this trio. A mutual friend recently lent Conan and I a bunch of comics (City of Glass, The Death Ray), which helped boost my book quota. The G.N.B. Double C comes in at an auspicious Number 40.At first, I wasn’t really sure what I was reading – was it fact or fiction? I expressed my confusion to Olman, who told me to keep reading, as this is “Seth’s conceit”, to create a fictional universe where cartoons are revered like works of art. To quote The Comics Journal, Seth “deftly mixes real and imagined cartoon history in its depiction of a fictional cartoon society in the city of Dominion, where artists from every facet of the medium once gathered to drink, carouse, and sometimes even discuss cartooning.”

The book has an appealing old school hardcover, and there is a nicely crafted quality to the overall design and narrative, yet I wasn’t particularly fond of the cartoon style within. I think Seth succeeded too well in invoking the thick-lined, squat-figured cartoons of old. I just didn’t find the old-time, cornballish style very graceful or aesthetically interesting.

This National review did a good job explaining this oddball comic, but the opinion of the reviewer was not very clear. For myself, I liked this comic ok, and it was indeed a neat conceit. But it just didn’t really do much for me. I think I might enjoy Seth’s other work, like Palookaville or Clyde Fans, so I will have to see if Olman or Dan has any of those comics.

Saturday, December 03, 2011

Book 39 – The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest

By Stieg Larsson

Well-- it’s been over year since I became The Girl Who Kicked Herself For Not Getting The Cheap Hardcover at Chainon.

Last we left off with the exciting conclusion of The Girl Who Played With Fire, Lisbeth Salander was shot in the head by her estranged Pa, her semi-conscious body airlifted to the nearest hospital. Even though you know our heroine is going to pull through somehow, it was still one hell of a cliffhanger to nurse for a year and three months. When hubs got me an iPad last Xmas, I was tempted to get the e-book, but thought the $11 price tag was a little steep. Now that it’s finally released in paperback (for $8! so Why-TF was the e-version more expensive?), I promptly ordered a copy.

Lemme tell ya, it was well worth the wait, despite the fact that this 563–page action-packed tome kept me up multiple nights in a row. To quote that silly line from the new Cronenberg movie: “It excited me!”

Unlike the majority of trilogies or series where each sequel is like a watered-down and/or inferior version of the original (take The Dark Materials trilogy, for instance), each installment of the Millenium trilogy was better than the last. I liked The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo all right, but The Girl Who Played With Fire took it to the next level, focusing on the character development of the fascinating Lisbeth Salander, as well as allowing her to kick even more ass (physical and cyber-spatial) than before.

The second book also introduced a whole web of new characters and how they were all inter-related to one another. Of course, the common denominator was The Girl herself, but there were new writers working for Millenium, various police inspectors, government officials, secret police agents, biker gang members, old friends of Lisbeth, as well as not-so-friendly people from her tragic past.

The third book has many of the same characters, and then some. It’s like a crazy Swedish version of The Wire, except we have a young woman entangled in some secret government conspiracy to have her locked away in an institution for life. And all because her father happens to be a badass Russian defector and ex-spy who keeps getting into trouble with the authorities because he's an underworld gangster as well as a wife-beater!

Despite the fact that Salander is not able to kick as much ass as she did in the previous book (due to her recovering from a bullet hole in the head (--oops I gave it away, oh well!), Salander’s motley crue of unlikely allies (a few who have friends in strategic places) rise to the occasion to help her out of this conspiracy mess, and Lisbeth also turns to her comrades at the exclusive Hacker Republic for help. The plot of TGWKTHN has been criticized for being preposterous, which is ridiculous. I mean, the Millenium trilogy from the get-go has been about as realistic as, say, the Bourne books. This is escapist fiction, for chrissakes, and other than the not so subtle theme of Men Hating Women, these books aren’t pretending to be anything more. If you want to read a more realistic story, then go read some Margaret Atwood or something.

More importantly, despite the phenomenal number of subplots and characters, Larsson managed to tie everything together into something that was competently cohesive. There was a whole other seemingly unrelated subplot where Erika Berger quit Millenium to work as editor-in-chief for the major newspaper, SMP, and within the first two weeks of her new job, conventiently acquired a stalker. That storyline could have been cut out, but at the same time, it felt like it fit into the narrative, logistically and thematically. It could’ve been a structural mess in the hands of a less disciplined writer. As an experienced journalist, Larsson also did a great job writing about the bustling newsroom of a major daily, the inner workings of Swedish governmental politics or a general overview of constitutional laws. The complicated plot allowed Larsson to touch on various aspects of Swedish society, from the high-ranking offices of CEOs and government officials to some shabby apartment of a lowly drug dealer.

Even if you think the story was rather preposterous, Larsson grounded his universe in such a confident, straightforward maner that you won’t immediately realize how much info you’ve been absorbing at once… that is, until you’re having a fitful night of sleep as the various elements from the novel float about inside your head! Even after more than a year between the 2nd and 3rd books, I was able to remember many of the plot points and characters. I think, after reading the Millenium books, everyone becomes a little like Lisbeth Salander, with her photographic memory and careful observation of details. And the finale was awesome. There were no loose strings I could find.

Immediately after finishing The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest, Olman and I watched the movie version, which was rather hurried, omitting tons of details and subplots. A few times Olman went “huh?” after the movie skipped or altered something from the book. Since he hasn’t read the Millenium books, I had to fill him in on some background info. So if you’re gonna watch the last movie, it might not make as much sense if you haven’t read the final book. It might have been worthwhile to split the book into two parts, like what they did with Twilight and Harry Potter. Let’s hope the American remake will do this!

Well-- it’s been over year since I became The Girl Who Kicked Herself For Not Getting The Cheap Hardcover at Chainon.

Last we left off with the exciting conclusion of The Girl Who Played With Fire, Lisbeth Salander was shot in the head by her estranged Pa, her semi-conscious body airlifted to the nearest hospital. Even though you know our heroine is going to pull through somehow, it was still one hell of a cliffhanger to nurse for a year and three months. When hubs got me an iPad last Xmas, I was tempted to get the e-book, but thought the $11 price tag was a little steep. Now that it’s finally released in paperback (for $8! so Why-TF was the e-version more expensive?), I promptly ordered a copy.

Lemme tell ya, it was well worth the wait, despite the fact that this 563–page action-packed tome kept me up multiple nights in a row. To quote that silly line from the new Cronenberg movie: “It excited me!”

Unlike the majority of trilogies or series where each sequel is like a watered-down and/or inferior version of the original (take The Dark Materials trilogy, for instance), each installment of the Millenium trilogy was better than the last. I liked The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo all right, but The Girl Who Played With Fire took it to the next level, focusing on the character development of the fascinating Lisbeth Salander, as well as allowing her to kick even more ass (physical and cyber-spatial) than before.

The second book also introduced a whole web of new characters and how they were all inter-related to one another. Of course, the common denominator was The Girl herself, but there were new writers working for Millenium, various police inspectors, government officials, secret police agents, biker gang members, old friends of Lisbeth, as well as not-so-friendly people from her tragic past.

The third book has many of the same characters, and then some. It’s like a crazy Swedish version of The Wire, except we have a young woman entangled in some secret government conspiracy to have her locked away in an institution for life. And all because her father happens to be a badass Russian defector and ex-spy who keeps getting into trouble with the authorities because he's an underworld gangster as well as a wife-beater!

Despite the fact that Salander is not able to kick as much ass as she did in the previous book (due to her recovering from a bullet hole in the head (--oops I gave it away, oh well!), Salander’s motley crue of unlikely allies (a few who have friends in strategic places) rise to the occasion to help her out of this conspiracy mess, and Lisbeth also turns to her comrades at the exclusive Hacker Republic for help. The plot of TGWKTHN has been criticized for being preposterous, which is ridiculous. I mean, the Millenium trilogy from the get-go has been about as realistic as, say, the Bourne books. This is escapist fiction, for chrissakes, and other than the not so subtle theme of Men Hating Women, these books aren’t pretending to be anything more. If you want to read a more realistic story, then go read some Margaret Atwood or something.

More importantly, despite the phenomenal number of subplots and characters, Larsson managed to tie everything together into something that was competently cohesive. There was a whole other seemingly unrelated subplot where Erika Berger quit Millenium to work as editor-in-chief for the major newspaper, SMP, and within the first two weeks of her new job, conventiently acquired a stalker. That storyline could have been cut out, but at the same time, it felt like it fit into the narrative, logistically and thematically. It could’ve been a structural mess in the hands of a less disciplined writer. As an experienced journalist, Larsson also did a great job writing about the bustling newsroom of a major daily, the inner workings of Swedish governmental politics or a general overview of constitutional laws. The complicated plot allowed Larsson to touch on various aspects of Swedish society, from the high-ranking offices of CEOs and government officials to some shabby apartment of a lowly drug dealer.

Even if you think the story was rather preposterous, Larsson grounded his universe in such a confident, straightforward maner that you won’t immediately realize how much info you’ve been absorbing at once… that is, until you’re having a fitful night of sleep as the various elements from the novel float about inside your head! Even after more than a year between the 2nd and 3rd books, I was able to remember many of the plot points and characters. I think, after reading the Millenium books, everyone becomes a little like Lisbeth Salander, with her photographic memory and careful observation of details. And the finale was awesome. There were no loose strings I could find.

Immediately after finishing The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest, Olman and I watched the movie version, which was rather hurried, omitting tons of details and subplots. A few times Olman went “huh?” after the movie skipped or altered something from the book. Since he hasn’t read the Millenium books, I had to fill him in on some background info. So if you’re gonna watch the last movie, it might not make as much sense if you haven’t read the final book. It might have been worthwhile to split the book into two parts, like what they did with Twilight and Harry Potter. Let’s hope the American remake will do this!

Friday, December 02, 2011

Book 38 – The Death-Ray

By Daniel Clowes

Originally published in 2004 as a stand-alone issue of the Eightball series, The Death-Ray was recently reprinted as a nicely bound hardcover edition from Drawn & Quarterly. Shortly after reading a review of this release, a copy was loaned to Olman via my coworker (thanks Dan!).

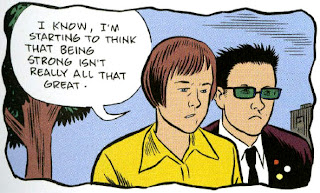

I don’t believe I’ve ever read anything by Clowes, though I very much liked the charmingly sarcastic movies version of Ghost World. All I know is that The Death-Ray is Clowes’ first and only stab at the superhero genre. Perhaps it would be better described as a “stab and twist” since there is a definite subversion of form. However, despite the pastel palette of the colour illustrations, there is hardly any humour to be found, only existential emptiness.

The story is basically about an ordinary and awkward teenaged boy in the 1970’s who grows up to be a lonely bitter man. Andy has the ability to be bestowed with superhuman strength when his body absorbs nicotine by simply smoking a cigarette. The death-ray is the gun he inherits from his odd, scientist father long after he had passed away. Just a single pull of the trigger will zap any living organism into non-existence.

Unlike Spider Man, great power does not come with great responsibility for our young Andy. He doesn’t blossom into a ripped example of sparkling masculinity but keeps his 90-pound weakling physique. Nor does he rise up to save the world from evil. Like any naive teenaged loser, Andy doesn’t quite abuse his power, but he definitely misuses it. Let’s just say this sad sack falls short of living up to any superhero potential, using his rather extraordinary gifts to solve his sadly ordinary problems. It’s a great premise to explore, and I’m sure the upcoming movie, Chronicle, was probably influenced to some extent by this comic.

Though I found the concept of The Death-Ray very interesting, I’m not sure if I liked it as much as, say, Charles Burns’ Black Hole, a comic which also explores the teenage psyche in 1970’s American suburbia in a supernatural manner. But it’s a little like comparing apples and oranges since The Death-Ray was a one-off, while Black Hole was the result of a ten-year effort. But I had felt so immersed in the dark, surreal universe of Black Hole, while The Death-Ray was like dipping into a wading pool by comparison. The brevity of The Death-Ray does not seem allow enough time for Clowes’ to explore his themes with any real depth.

The way Clowes’ jumps in time from panel to panel was probably intentional, but it felt quite disjointed to me. For example, after Andy discovers his new found powers, he decides to confront a school bully when he’s picking on his best friend Louie. All of a sudden, the next panel just shows Andy's bloodied hand, but never follows up on the bully. This happens fairly often throughout the comic. You never see the consequences when Andy decides to use violence against violence. I don’t mind jump cuts in movies, if they work for the story, and it can work visually in comics. Perhaps I am missing some kind of important symbolism that Clowes is trying to get at, but I found the panel jump a little annoying in The Death-Ray.

On the other hand, D&Q did a very professional job with the quality of the hardcover edition. The paper feels nice and thick, and shows off Clowes’ coloured illustrations well. And twenty bucks is a pretty reasonable price if you’re a fan of Clowes' work.

Originally published in 2004 as a stand-alone issue of the Eightball series, The Death-Ray was recently reprinted as a nicely bound hardcover edition from Drawn & Quarterly. Shortly after reading a review of this release, a copy was loaned to Olman via my coworker (thanks Dan!).

I don’t believe I’ve ever read anything by Clowes, though I very much liked the charmingly sarcastic movies version of Ghost World. All I know is that The Death-Ray is Clowes’ first and only stab at the superhero genre. Perhaps it would be better described as a “stab and twist” since there is a definite subversion of form. However, despite the pastel palette of the colour illustrations, there is hardly any humour to be found, only existential emptiness.

The story is basically about an ordinary and awkward teenaged boy in the 1970’s who grows up to be a lonely bitter man. Andy has the ability to be bestowed with superhuman strength when his body absorbs nicotine by simply smoking a cigarette. The death-ray is the gun he inherits from his odd, scientist father long after he had passed away. Just a single pull of the trigger will zap any living organism into non-existence.

Unlike Spider Man, great power does not come with great responsibility for our young Andy. He doesn’t blossom into a ripped example of sparkling masculinity but keeps his 90-pound weakling physique. Nor does he rise up to save the world from evil. Like any naive teenaged loser, Andy doesn’t quite abuse his power, but he definitely misuses it. Let’s just say this sad sack falls short of living up to any superhero potential, using his rather extraordinary gifts to solve his sadly ordinary problems. It’s a great premise to explore, and I’m sure the upcoming movie, Chronicle, was probably influenced to some extent by this comic.

Though I found the concept of The Death-Ray very interesting, I’m not sure if I liked it as much as, say, Charles Burns’ Black Hole, a comic which also explores the teenage psyche in 1970’s American suburbia in a supernatural manner. But it’s a little like comparing apples and oranges since The Death-Ray was a one-off, while Black Hole was the result of a ten-year effort. But I had felt so immersed in the dark, surreal universe of Black Hole, while The Death-Ray was like dipping into a wading pool by comparison. The brevity of The Death-Ray does not seem allow enough time for Clowes’ to explore his themes with any real depth.

The way Clowes’ jumps in time from panel to panel was probably intentional, but it felt quite disjointed to me. For example, after Andy discovers his new found powers, he decides to confront a school bully when he’s picking on his best friend Louie. All of a sudden, the next panel just shows Andy's bloodied hand, but never follows up on the bully. This happens fairly often throughout the comic. You never see the consequences when Andy decides to use violence against violence. I don’t mind jump cuts in movies, if they work for the story, and it can work visually in comics. Perhaps I am missing some kind of important symbolism that Clowes is trying to get at, but I found the panel jump a little annoying in The Death-Ray.

On the other hand, D&Q did a very professional job with the quality of the hardcover edition. The paper feels nice and thick, and shows off Clowes’ coloured illustrations well. And twenty bucks is a pretty reasonable price if you’re a fan of Clowes' work.

Labels:

comic,

daniel clowes,

ghost world,

graphic novel,

superhero,

the death-ray

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

Book 37 – City of Glass: the Graphic Novel

By Paul Auster

Adaptation by Paul Karasik and David Mazzucchelli

I had read Paul Auster’s New York Trilogy a few years ago as separate books (City of Glass, Ghosts, and The Locked Room). My review did not provide any plot summary, so I don’t remember much except the exquisite atmosphere of dreamy dread that permeated each book. And that I really liked them. This turned out to be advantageous since the 1994 comic adaptation of City of Glass recently fell into my hands thanks to my coworker via Olman (the copy was the 2004 Picador edition). Reading the comic made me remember everything about the original novella as I went along, so it was almost like re-experiencing the story in a new way.

As Art Spiegelman mentioned in his introduction, I was impressed with how Karasik and Mazzucchelli created such an effective comic out of a strange and metaphysical work as City of Glass, which apparently posed a challenge for many to visualize (there have been a number of unsuccessful attempts to adapt it as a screenplay).

City of Glass starts off as a fairly straightforward detective mystery, though with a pervasive feeling that something is a little off. At some point, the narrative becomes unhinged and takes a turn toward po-mo existentialism, but compellingly so. I always wondered what City of Glass would’ve been like had Auster stuck to genre conventions because I think it would’ve made a great detective story. But that’s crazy talk since part of the story’s power lies in its deconstruction of narrative and character. After all, City of Glass is one of many novels where Auster explores his trademark themes: the disintegration of reality and identity.

Paul Karasik and David Mazzucchelli were able to take those trademark Auster themes and visualize them in comic form. They utilized everything they knew about the art of comics into City of Glass, but each panel is designed in a very controlled and thoughtful way. It is a wonderful synthesis of two different but complementary mediums. For anyone interested in a deeper analysis of how Karasik & Mazzuchhelli translate prose to the comic form, take a look at this blog.

If you haven’t read the original novel or the comic adaptation, then I would recommend reading the novel first then waiting a long while before reading the comic. Like long enough to not remember any details of the novel (say a few years!). But if you lack the discipline and cannot wait that long, then I liked what this Guardian review had to say about this little quandary:

If you haven't read City of Glass, then you have an intriguing dilemma: not which of the two books to read - you should read both - but which to read first. I can't really answer that question, because setting them against one another, trying to decide which is more successful, seems pointless. Both are wonderful works of art. Both are worth reading again and again. And each complements the other, the comic driving you back the novel, and vice versa.

Adaptation by Paul Karasik and David Mazzucchelli

I had read Paul Auster’s New York Trilogy a few years ago as separate books (City of Glass, Ghosts, and The Locked Room). My review did not provide any plot summary, so I don’t remember much except the exquisite atmosphere of dreamy dread that permeated each book. And that I really liked them. This turned out to be advantageous since the 1994 comic adaptation of City of Glass recently fell into my hands thanks to my coworker via Olman (the copy was the 2004 Picador edition). Reading the comic made me remember everything about the original novella as I went along, so it was almost like re-experiencing the story in a new way.

As Art Spiegelman mentioned in his introduction, I was impressed with how Karasik and Mazzucchelli created such an effective comic out of a strange and metaphysical work as City of Glass, which apparently posed a challenge for many to visualize (there have been a number of unsuccessful attempts to adapt it as a screenplay).

City of Glass starts off as a fairly straightforward detective mystery, though with a pervasive feeling that something is a little off. At some point, the narrative becomes unhinged and takes a turn toward po-mo existentialism, but compellingly so. I always wondered what City of Glass would’ve been like had Auster stuck to genre conventions because I think it would’ve made a great detective story. But that’s crazy talk since part of the story’s power lies in its deconstruction of narrative and character. After all, City of Glass is one of many novels where Auster explores his trademark themes: the disintegration of reality and identity.

Paul Karasik and David Mazzucchelli were able to take those trademark Auster themes and visualize them in comic form. They utilized everything they knew about the art of comics into City of Glass, but each panel is designed in a very controlled and thoughtful way. It is a wonderful synthesis of two different but complementary mediums. For anyone interested in a deeper analysis of how Karasik & Mazzuchhelli translate prose to the comic form, take a look at this blog.

If you haven’t read the original novel or the comic adaptation, then I would recommend reading the novel first then waiting a long while before reading the comic. Like long enough to not remember any details of the novel (say a few years!). But if you lack the discipline and cannot wait that long, then I liked what this Guardian review had to say about this little quandary:

If you haven't read City of Glass, then you have an intriguing dilemma: not which of the two books to read - you should read both - but which to read first. I can't really answer that question, because setting them against one another, trying to decide which is more successful, seems pointless. Both are wonderful works of art. Both are worth reading again and again. And each complements the other, the comic driving you back the novel, and vice versa.

Thursday, November 24, 2011

Book 36 - Tokyo On Foot: A Graphic Memoir

By Florent Chavouet

This was one of those rare impulsive purchases when I was at Drawn & Quarterly. Though I didn’t have any luck finding a birthday gift for a friend, I had no trouble spotting something I wanted for myself, as my eye was immediately drawn to the cover of Tokyo On Foot, the last English copy in the store (the original version is in French).

Having visited Japan over a decade ago, leafing through Chavouet’s images evoked warm, fuzzy feelings of that memorable trip, hence the impulsive purchase. This was also the book I sought solace in when I wanted to momentarily escape from exploring the human capacity for war and violence in Three Day Road.

Chavouet is a French graphic artist who moved to Japan with his girlfriend when she landed a one year internship at an unnamed company. The more accurate title would have been "Tokyo By Bike". When Chavouet wasn’t trying to find the odd job as a French waiter, he'd bike to an unexplored area of Tokyo with his portable chair, stopping to sketch something interesting.

His subjects range from random people on the street who’d stop and check out what he’s drawing to a run-down house that stuck out like a sore thumb across the street, or maybe a jumbled view of shops and noodle houses within a city block, or a secluded spot in a park away from the urban hullabaloo.

The hand-drawn maps of each neighbourhood (21 in total) are amazingly intricate, yet useful if you were to use the maps to trace his daily route. Each chapter begins with a map of the district or prefecture with highlights of the various spots where he stops to capture the scenery. Each highlight has a page number so you can find the sketch of what took his fancy and sometimes there are charming little captions or annotations to explain what he observed.

Reading some reviews on Goodreads, there were a few complaints how the book is only an outsider’s superficial interpretation of Tokyo, and Chavouet never learned more than a few Japanese phrases. Well, yeah, the guy did only spend a year there. He’s an illustrator, not a scholar or journalist. I felt that part of the appeal was that his drawings are exactly that, a view from an outsider’s perspective. Chavouet’s art contains a mixture of curiosity, interest, amusement, bemusement and/or mild dislocation. Perhaps his interpretations are not always accurate, but they seem genuine in feeling.

I also really enjoyed his profiles of random people’s fashion styles on the street, such as this cross-section of Shibuya:

Here’s a review which pretty much explains more articulately how I felt about it.

And this blog gives a good idea of what it's like flipping through Tokyo On Foot.

This was one of those rare impulsive purchases when I was at Drawn & Quarterly. Though I didn’t have any luck finding a birthday gift for a friend, I had no trouble spotting something I wanted for myself, as my eye was immediately drawn to the cover of Tokyo On Foot, the last English copy in the store (the original version is in French).

Having visited Japan over a decade ago, leafing through Chavouet’s images evoked warm, fuzzy feelings of that memorable trip, hence the impulsive purchase. This was also the book I sought solace in when I wanted to momentarily escape from exploring the human capacity for war and violence in Three Day Road.

Chavouet is a French graphic artist who moved to Japan with his girlfriend when she landed a one year internship at an unnamed company. The more accurate title would have been "Tokyo By Bike". When Chavouet wasn’t trying to find the odd job as a French waiter, he'd bike to an unexplored area of Tokyo with his portable chair, stopping to sketch something interesting.

His subjects range from random people on the street who’d stop and check out what he’s drawing to a run-down house that stuck out like a sore thumb across the street, or maybe a jumbled view of shops and noodle houses within a city block, or a secluded spot in a park away from the urban hullabaloo.

The hand-drawn maps of each neighbourhood (21 in total) are amazingly intricate, yet useful if you were to use the maps to trace his daily route. Each chapter begins with a map of the district or prefecture with highlights of the various spots where he stops to capture the scenery. Each highlight has a page number so you can find the sketch of what took his fancy and sometimes there are charming little captions or annotations to explain what he observed.

Reading some reviews on Goodreads, there were a few complaints how the book is only an outsider’s superficial interpretation of Tokyo, and Chavouet never learned more than a few Japanese phrases. Well, yeah, the guy did only spend a year there. He’s an illustrator, not a scholar or journalist. I felt that part of the appeal was that his drawings are exactly that, a view from an outsider’s perspective. Chavouet’s art contains a mixture of curiosity, interest, amusement, bemusement and/or mild dislocation. Perhaps his interpretations are not always accurate, but they seem genuine in feeling.

I also really enjoyed his profiles of random people’s fashion styles on the street, such as this cross-section of Shibuya:

Here’s a review which pretty much explains more articulately how I felt about it.

And this blog gives a good idea of what it's like flipping through Tokyo On Foot.

Labels:

Florent Chavouet,

graphic memoir,

japan,

tokyo on foot

Monday, November 21, 2011

Book 35 – Uglies

By Scott Westerfeld

I’ve officially broken last year’s record with my 35th book. Yay.

Uglies was on my “maybe to read” list since it’s a futuristic dystopian young adult novel that received mixed reviews. When I found a cheap copy at my good ol’ reliable thrift shop, I thought it would make a quick n’ easy read (as I’m still aiming to read 40 books this year). And it turned out to be the case indeed!

The premise sounds intriguing enough. A few hundred years after some mysterious catastrophe obliterated the world’s oil supply (thus ending human civilization as we know it), society has rebuilt itself by harnessing renewable energy resources and going vegan. Technology has evolved to sustain and populate the cities again. Isolated and self-sufficient yet also fearful of war and dissent, these eco-friendly cities hit upon the need to create standards for the greater good.

Societal ills largely stem from people having vast differences over things like status and wealth, but obviously, not everyone can be rich and fabulous. And going all communist and making everyone poor wouldn’t be very fun either. But since everyone is born with inherent flaws in their physical appearance, wouldn’t the world be a happier place if everyone were beautiful? And even better, beautiful and blissfully ignorant! It would be the perfect equalizer!

When children turn 16, the benevolent government bestows upon them a series of extreme surgeries to have their faces and bodies (among other things) molded to fit societal standards of perfect beauty. Since humans are evolutionarily preconditioned to have positive responses to facial symmetry, clear complexions and proportionate bodies, applying these standards equally for everyone will reduce conflict and create a more harmonious society. By agreeing to go under the knife, you are also rewarded by getting to party every day and every night (at least until it's time to reproduce) with all the fancy clothes and cosmos you could possibly want!

Westerfeld thus takes a page off of Dystopian Fiction 101 where you have a “vision of an orderly world in which suffering is minimized and pleasure maximized”. But for me, it is only a partially complete world. As a science fiction novel, the author does not explain how a society (even one with highly advanced technology) can support a whole class of perfectly sculpted hedonists (like who makes their disposable fancy clothes or distills the alcohol that gets them loaded?), nor how it can sustain itself when the majority of its young citizens are partying during their stage of post-educational development instead of working towards being productive members of society (like cosmetic surgeons, for instance). But this pretty little book does not want to bother with such trivial details.

Instead we have a world where everyone is supermodel-gorgeous, so now normal people seem ugly by comparison (one wonders what this world would do with the truly hideous or deformed but, surprise, the book doesn't bother with that either). Children are considered Littlies and therefore exempt from being ugly. As soon as they turn twelve, they are relegated to official “Ugly” status, spending the next four years loathing themselves and longing to be “Pretty”. Sound familiar?

Westerfeld has put a clever spin on the awkward stage of adolescence, but I still found Uglies rather "meh". There just wasn’t anything particularly original or refreshing in the themes, nor in the execution of those themes. We have some dystopian teen angst embodied in fifteen-year-old protagonist Tally Youngblood, and there is the obvious social commentary about how society perpetuates unrealistic images of beauty to our youth. But it doesn’t go beyond, well, the obvious.

What happens to young naive Tally Youngblood is also pretty rote stuff, so I won’t get into how Tally loses her best friend Peris once he becomes a Pretty, then finds a new BFF in rebellious Shay, who convinces Tally to journey to the Rusty Ruins which leads her to a band of merry Uglies living in a secluded mountain valley (as well as fall for the same boy named David who is -surprise!- actually pretty cute for "ugly" standards). To Tally’s amazement, David and his fellow Uglies don’t see themselves as ugly at all. They are content to live out their lives without any surgical intervention imposed on their bodies. Imagine that!

It’s no surprise that the "urban dystopia versus utopian wilderness" theme has become somewhat clichéd: people are unwittingly domesticated by a [enter –ist word, ie. fascist, agist, uglist] society, yet one individual manages to see through the false utopia, escapes to discover an alternate community of [enter synonym for dissenters, counter-culture types, etc.] who eventually overcome the system, and reclaim humanity. I have not read much dystopian fiction, but already Logan’s Run (1967) and John Christopher’s Wild Jack (1974) come to mind. The Hunger Games is another recent example which recycles familiar tropes, but the excellent pacing and tight narrative makes you forgive some inherent flaws. More importantly, the world that Suzanne Collins depicts feels more complete. There are no gaping logistical holes that fester in the back of your mind, like it did for me when reading Uglies.

For whatever reason, I didn’t get the same thrill and enjoyment with Uglies. For one thing, I couldn’t get past the cutesy terms for categorizing people: Littlies, Uglies, New Pretties, Middle Pretties and Late Pretties (or Crumblies). I mean, where are the SILLIES when you need ‘em? Ok, there are the Specials, but they should really be called the SCARIES, since they are government agents surgically enhanced for intelligence, strength and, wait for it, terrifying beauty. Let’s not forget the people of old who used to live in pollution-choked cities and kill animals for food. They were known as the Rusties. Nothing is too complicated that would potentially hurt a reader's pretty little head.

Westerfeld, however, does do a decent job capturing the mentality of a typical teenage girl growing up in a screwed up world. Tally’s guilt for being a potential traitor to the cause is also portrayed quite realistically, as you definitely get the sense that our heroine is a naive character who has a LOT to learn and develops some backbone and principles toward the end. At the end of the day, though, Westerfeld's bland writing style combined with fairly half-baked ideas made Uglies seem like a book aimed at the lowest common denominator.

It’s too bad I don’t feel inclined to read the rest of the series, as it would help get me closer to 40 books!

I’ve officially broken last year’s record with my 35th book. Yay.

Uglies was on my “maybe to read” list since it’s a futuristic dystopian young adult novel that received mixed reviews. When I found a cheap copy at my good ol’ reliable thrift shop, I thought it would make a quick n’ easy read (as I’m still aiming to read 40 books this year). And it turned out to be the case indeed!

The premise sounds intriguing enough. A few hundred years after some mysterious catastrophe obliterated the world’s oil supply (thus ending human civilization as we know it), society has rebuilt itself by harnessing renewable energy resources and going vegan. Technology has evolved to sustain and populate the cities again. Isolated and self-sufficient yet also fearful of war and dissent, these eco-friendly cities hit upon the need to create standards for the greater good.

Societal ills largely stem from people having vast differences over things like status and wealth, but obviously, not everyone can be rich and fabulous. And going all communist and making everyone poor wouldn’t be very fun either. But since everyone is born with inherent flaws in their physical appearance, wouldn’t the world be a happier place if everyone were beautiful? And even better, beautiful and blissfully ignorant! It would be the perfect equalizer!

When children turn 16, the benevolent government bestows upon them a series of extreme surgeries to have their faces and bodies (among other things) molded to fit societal standards of perfect beauty. Since humans are evolutionarily preconditioned to have positive responses to facial symmetry, clear complexions and proportionate bodies, applying these standards equally for everyone will reduce conflict and create a more harmonious society. By agreeing to go under the knife, you are also rewarded by getting to party every day and every night (at least until it's time to reproduce) with all the fancy clothes and cosmos you could possibly want!

Westerfeld thus takes a page off of Dystopian Fiction 101 where you have a “vision of an orderly world in which suffering is minimized and pleasure maximized”. But for me, it is only a partially complete world. As a science fiction novel, the author does not explain how a society (even one with highly advanced technology) can support a whole class of perfectly sculpted hedonists (like who makes their disposable fancy clothes or distills the alcohol that gets them loaded?), nor how it can sustain itself when the majority of its young citizens are partying during their stage of post-educational development instead of working towards being productive members of society (like cosmetic surgeons, for instance). But this pretty little book does not want to bother with such trivial details.

Instead we have a world where everyone is supermodel-gorgeous, so now normal people seem ugly by comparison (one wonders what this world would do with the truly hideous or deformed but, surprise, the book doesn't bother with that either). Children are considered Littlies and therefore exempt from being ugly. As soon as they turn twelve, they are relegated to official “Ugly” status, spending the next four years loathing themselves and longing to be “Pretty”. Sound familiar?

Westerfeld has put a clever spin on the awkward stage of adolescence, but I still found Uglies rather "meh". There just wasn’t anything particularly original or refreshing in the themes, nor in the execution of those themes. We have some dystopian teen angst embodied in fifteen-year-old protagonist Tally Youngblood, and there is the obvious social commentary about how society perpetuates unrealistic images of beauty to our youth. But it doesn’t go beyond, well, the obvious.

What happens to young naive Tally Youngblood is also pretty rote stuff, so I won’t get into how Tally loses her best friend Peris once he becomes a Pretty, then finds a new BFF in rebellious Shay, who convinces Tally to journey to the Rusty Ruins which leads her to a band of merry Uglies living in a secluded mountain valley (as well as fall for the same boy named David who is -surprise!- actually pretty cute for "ugly" standards). To Tally’s amazement, David and his fellow Uglies don’t see themselves as ugly at all. They are content to live out their lives without any surgical intervention imposed on their bodies. Imagine that!

It’s no surprise that the "urban dystopia versus utopian wilderness" theme has become somewhat clichéd: people are unwittingly domesticated by a [enter –ist word, ie. fascist, agist, uglist] society, yet one individual manages to see through the false utopia, escapes to discover an alternate community of [enter synonym for dissenters, counter-culture types, etc.] who eventually overcome the system, and reclaim humanity. I have not read much dystopian fiction, but already Logan’s Run (1967) and John Christopher’s Wild Jack (1974) come to mind. The Hunger Games is another recent example which recycles familiar tropes, but the excellent pacing and tight narrative makes you forgive some inherent flaws. More importantly, the world that Suzanne Collins depicts feels more complete. There are no gaping logistical holes that fester in the back of your mind, like it did for me when reading Uglies.

For whatever reason, I didn’t get the same thrill and enjoyment with Uglies. For one thing, I couldn’t get past the cutesy terms for categorizing people: Littlies, Uglies, New Pretties, Middle Pretties and Late Pretties (or Crumblies). I mean, where are the SILLIES when you need ‘em? Ok, there are the Specials, but they should really be called the SCARIES, since they are government agents surgically enhanced for intelligence, strength and, wait for it, terrifying beauty. Let’s not forget the people of old who used to live in pollution-choked cities and kill animals for food. They were known as the Rusties. Nothing is too complicated that would potentially hurt a reader's pretty little head.

Westerfeld, however, does do a decent job capturing the mentality of a typical teenage girl growing up in a screwed up world. Tally’s guilt for being a potential traitor to the cause is also portrayed quite realistically, as you definitely get the sense that our heroine is a naive character who has a LOT to learn and develops some backbone and principles toward the end. At the end of the day, though, Westerfeld's bland writing style combined with fairly half-baked ideas made Uglies seem like a book aimed at the lowest common denominator.

It’s too bad I don’t feel inclined to read the rest of the series, as it would help get me closer to 40 books!

Tuesday, November 15, 2011

Book 34 – Three Day Road

By Joseph Boyden

It’s hard to imagine that Three Day Road is Boyden’s first novel. Not only is it ambitious in scope, it’s remarkably cohesive for its unusual narrative structure and quite gracefully written too (as Kate also noted in her review). However the ambitiousness of the novel is not meant to impress (like Cloud Atlas, for instance), but instead bring to life voices not commonly heard and stories often overlooked by history.

The heart of the novel is centred on thre friendship between Xavier Bird and Elijah Whiskeyjack, young Cree men who voluntarily enlist and become legendary snipers in Europe during the Great War. They leave behind Xavier’s aunt Niska, a medicine woman who, having avoided assimilation, raised both boys in the Oji-Cree tradition in the wilds of Northern Ontario. The story begins after the war is over when Xavier returns home to Niska, physically and emotionally damaged, and addicted to morphine. As aunt and nephew journey back to their camp by canoe, the narrative weaves between the voices of the three characters: Xavier reliving the nightmare of his war experiences in a morphine-induced fever, Elijah obsessively confessing to Xavier about his war exploits, and Niska reaching out to Xavier by telling him about her past. Within this cyclical structure, Boyden also attempts to evoke the Cree and Ojibwe tradition of storytelling.

As a more conventional narrative, Three Day Road has the potential to appeal to a range of readers in the way it taps into multiple experiences. If you’re interested in war history, the novel is a harrowing account of trench warfare yet on a smaller scale presents an intimate portrait of the modern sniper, whose skill is taken to a new level of specialty during WWI. If First Nations history is more your thing, the little known WWI hero, Francis "Peggy" Pegahmagabow, served as inspiration for the characters of Elijah and Xavier. This in itself is a great story premise because you have the combination of Native game hunters making the transition to deadly snipers, utilizing their skills on the battlefield to "devastating effect” with the narrative freedom of having them leave the confines of mud-filled trenches into more varied geography (from the Penguin Readers Guide).

To make it even more historically realistic, Boyden places Elijah and Xavier as infantry in the real-life Second Canadian Division, tracing their route throughout their three-year involvement in the war. The 2nd Division also participated in the Western Front’s most atrocious battles (like Passchendale), their victories having (ironically) helped put Canada on the international map. The novel is further enriched by the importance the role Native Canadian soldiers played in the conflict yet only to return home without any official recognition.

Three Day Road portrays the period of upheaval when Aboriginal Canadians were forced to assimilate into early 20th century European-Canadian society by separating children from their families and placing them in residential schools. Niska and Xavier managed to escape assimilation and live out in the bush, but Elijah was a product of a residential upbringing. Even though Elijah experienced some abuse at the hands of a nun, Boyden does not dwell on him as a victim, but rather, as a survivor making use of his Western education and English skills to gain favour with his division when he and Xavier are stationed in Europe.

Though much of the novel is grounded in historical reality, there are also elements of the supernatural woven into the tale. This is mostly due to Niska being the last of a lineage of shamans and windigo-killers. Some readers may be wary of this potential for cliché, but her character is nevertheless realistically portrayed as a strong, proud woman who maintains her independence and way of life while her people live in towns as second-class citizens and/or have succumbed to alcoholism.

This was the first time I’ve read about WW1 in a fictional work, and frankly, it's not a subject matter I would voluntarily read about. I remembered enough from my history classes to know how horrifying both World Wars were. Part of the reason why this book took a while for me to finish was because it was so very, very dark. There were many violent depictions of death yet each death was not treated lightly. As Kate mentioned in her review, “the strength and spirit of the characters really overpowered the dark stuff in a good way so that the book felt really balanced in its depiction of events”. But I still had to take the occasional break from the novel to read something else (which is too bad, as it would've been so fitting had I finished it for Remembrance Day on 11/11/11).

I was nevertheless impressed by Boyden’s meticulous research and skill as a writer. He brought to life all the gruesome details of trench warfare and the cultural genocide of aboriginals while at the same time avoided almost all the clichés associated with writing about those subjects in the “native voice”. Combined with the occasional magic realist touches, I admit Boyden did at times verge dangerously close to cliché, but overall he was able to pull it off without being too hokey. What was amazing was that he was able to make a believable symbolic connection between Niska’s background as a windigo-killer and the disintegrating friendship of Xavier and Elijah as the continuing war took its toll on their sanity. Hopefully I’m not revealing too much, but Boyden ties this all together quite effectively.

Overall There Day Road succeeds as a novel because it was a very personal work for the author. Having a grandfather who served in WWI and a father as a decorated medical officer in WWII, Boyden obviously has a vested personal interest in the history of war. Being of mixed Scottish, Irish and Metis heritage also gives Boyden a measure of legitimacy in writing from a First Nations perspective. I would definitely recommend Three Day Road for anyone interested in contemporary Canadian literature. Despite its moments of terrible darkness, it proved in the end to be a very rewarding and enlightening reading experience.

(p.s. was very siked to find a copy of this at my local thrift shop too)

It’s hard to imagine that Three Day Road is Boyden’s first novel. Not only is it ambitious in scope, it’s remarkably cohesive for its unusual narrative structure and quite gracefully written too (as Kate also noted in her review). However the ambitiousness of the novel is not meant to impress (like Cloud Atlas, for instance), but instead bring to life voices not commonly heard and stories often overlooked by history.

The heart of the novel is centred on thre friendship between Xavier Bird and Elijah Whiskeyjack, young Cree men who voluntarily enlist and become legendary snipers in Europe during the Great War. They leave behind Xavier’s aunt Niska, a medicine woman who, having avoided assimilation, raised both boys in the Oji-Cree tradition in the wilds of Northern Ontario. The story begins after the war is over when Xavier returns home to Niska, physically and emotionally damaged, and addicted to morphine. As aunt and nephew journey back to their camp by canoe, the narrative weaves between the voices of the three characters: Xavier reliving the nightmare of his war experiences in a morphine-induced fever, Elijah obsessively confessing to Xavier about his war exploits, and Niska reaching out to Xavier by telling him about her past. Within this cyclical structure, Boyden also attempts to evoke the Cree and Ojibwe tradition of storytelling.

As a more conventional narrative, Three Day Road has the potential to appeal to a range of readers in the way it taps into multiple experiences. If you’re interested in war history, the novel is a harrowing account of trench warfare yet on a smaller scale presents an intimate portrait of the modern sniper, whose skill is taken to a new level of specialty during WWI. If First Nations history is more your thing, the little known WWI hero, Francis "Peggy" Pegahmagabow, served as inspiration for the characters of Elijah and Xavier. This in itself is a great story premise because you have the combination of Native game hunters making the transition to deadly snipers, utilizing their skills on the battlefield to "devastating effect” with the narrative freedom of having them leave the confines of mud-filled trenches into more varied geography (from the Penguin Readers Guide).

To make it even more historically realistic, Boyden places Elijah and Xavier as infantry in the real-life Second Canadian Division, tracing their route throughout their three-year involvement in the war. The 2nd Division also participated in the Western Front’s most atrocious battles (like Passchendale), their victories having (ironically) helped put Canada on the international map. The novel is further enriched by the importance the role Native Canadian soldiers played in the conflict yet only to return home without any official recognition.

Three Day Road portrays the period of upheaval when Aboriginal Canadians were forced to assimilate into early 20th century European-Canadian society by separating children from their families and placing them in residential schools. Niska and Xavier managed to escape assimilation and live out in the bush, but Elijah was a product of a residential upbringing. Even though Elijah experienced some abuse at the hands of a nun, Boyden does not dwell on him as a victim, but rather, as a survivor making use of his Western education and English skills to gain favour with his division when he and Xavier are stationed in Europe.

Though much of the novel is grounded in historical reality, there are also elements of the supernatural woven into the tale. This is mostly due to Niska being the last of a lineage of shamans and windigo-killers. Some readers may be wary of this potential for cliché, but her character is nevertheless realistically portrayed as a strong, proud woman who maintains her independence and way of life while her people live in towns as second-class citizens and/or have succumbed to alcoholism.

This was the first time I’ve read about WW1 in a fictional work, and frankly, it's not a subject matter I would voluntarily read about. I remembered enough from my history classes to know how horrifying both World Wars were. Part of the reason why this book took a while for me to finish was because it was so very, very dark. There were many violent depictions of death yet each death was not treated lightly. As Kate mentioned in her review, “the strength and spirit of the characters really overpowered the dark stuff in a good way so that the book felt really balanced in its depiction of events”. But I still had to take the occasional break from the novel to read something else (which is too bad, as it would've been so fitting had I finished it for Remembrance Day on 11/11/11).

I was nevertheless impressed by Boyden’s meticulous research and skill as a writer. He brought to life all the gruesome details of trench warfare and the cultural genocide of aboriginals while at the same time avoided almost all the clichés associated with writing about those subjects in the “native voice”. Combined with the occasional magic realist touches, I admit Boyden did at times verge dangerously close to cliché, but overall he was able to pull it off without being too hokey. What was amazing was that he was able to make a believable symbolic connection between Niska’s background as a windigo-killer and the disintegrating friendship of Xavier and Elijah as the continuing war took its toll on their sanity. Hopefully I’m not revealing too much, but Boyden ties this all together quite effectively.

Overall There Day Road succeeds as a novel because it was a very personal work for the author. Having a grandfather who served in WWI and a father as a decorated medical officer in WWII, Boyden obviously has a vested personal interest in the history of war. Being of mixed Scottish, Irish and Metis heritage also gives Boyden a measure of legitimacy in writing from a First Nations perspective. I would definitely recommend Three Day Road for anyone interested in contemporary Canadian literature. Despite its moments of terrible darkness, it proved in the end to be a very rewarding and enlightening reading experience.

(p.s. was very siked to find a copy of this at my local thrift shop too)

Wednesday, October 26, 2011

Book 33 – Post Office

By Charles Bukowski

Amy's Used Books in Amherst, Nova Scotia was probably the most plentiful and least musty-smelling bookstore Olman and I have come across, at least in Canada. However, the over-abundance of books resulted in stacks taller than myself which obscured the alphabetaized books in the shelves. I won't go into detail about how I toppled a six-foot stack when I attempted to extract a copy of Post Office. Suffice to say I was rather surprised that a book by the Buk wasn’t displayed behind the cashier. In fact the book (which was in great condition) was like six bucks (I saw the same used copy online asking for twenty-something euros). So I thought it was a good find.

As the title suggests, Post Office chronicles the sordid life of Bukoswki’s alter ego Henry Chinaski when he lands a job as a substitute for the U.S. Postal Service. And what a miserable job it is. When he is not nursing another hungover at work, Chinaski is either chasing tail, getting gassed or betting on horses. If it's a good day it's all of the above. I've always been midly curious about Bukowski, and asked Olman if he had ever read anything by him. He said he tried reading his stuff back in college but couldn’t finish because he found it too sexist. I thought that was kind of funny considering the male-centric genre books Olman likes to read. I do admit it was at times offputting the way Chinaski regards every female he encounters as potential lays and how he ogles a woman's breasts before even looking at her eyes.

In any case, this is a book where the author’s reputation far precedes it. But I liked Post Office both for and despite its dated sexism, racism and self-destructivism. The fascistic and miserable environment of the post office is offset by the debauchery of the boozy, lusty Henry Chinaski. There is a colloquial deadpan style to the writing that is rather appealing, perhaps due to the fact that it might have been regarded as obscene at the time, but now comes off as rather quaint. But the heart of the novel is still there. Anyone, male or female, who has ever been stuck working at a shitty dead-end job can definitely relate to how soul-deadening it can be. Bukowski was probably one of the first writers to truly express this.

Here is a review that sums up more thoughtfully and eloquently how I felt about Post Office.

Amy's Used Books in Amherst, Nova Scotia was probably the most plentiful and least musty-smelling bookstore Olman and I have come across, at least in Canada. However, the over-abundance of books resulted in stacks taller than myself which obscured the alphabetaized books in the shelves. I won't go into detail about how I toppled a six-foot stack when I attempted to extract a copy of Post Office. Suffice to say I was rather surprised that a book by the Buk wasn’t displayed behind the cashier. In fact the book (which was in great condition) was like six bucks (I saw the same used copy online asking for twenty-something euros). So I thought it was a good find.

As the title suggests, Post Office chronicles the sordid life of Bukoswki’s alter ego Henry Chinaski when he lands a job as a substitute for the U.S. Postal Service. And what a miserable job it is. When he is not nursing another hungover at work, Chinaski is either chasing tail, getting gassed or betting on horses. If it's a good day it's all of the above. I've always been midly curious about Bukowski, and asked Olman if he had ever read anything by him. He said he tried reading his stuff back in college but couldn’t finish because he found it too sexist. I thought that was kind of funny considering the male-centric genre books Olman likes to read. I do admit it was at times offputting the way Chinaski regards every female he encounters as potential lays and how he ogles a woman's breasts before even looking at her eyes.

In any case, this is a book where the author’s reputation far precedes it. But I liked Post Office both for and despite its dated sexism, racism and self-destructivism. The fascistic and miserable environment of the post office is offset by the debauchery of the boozy, lusty Henry Chinaski. There is a colloquial deadpan style to the writing that is rather appealing, perhaps due to the fact that it might have been regarded as obscene at the time, but now comes off as rather quaint. But the heart of the novel is still there. Anyone, male or female, who has ever been stuck working at a shitty dead-end job can definitely relate to how soul-deadening it can be. Bukowski was probably one of the first writers to truly express this.

Here is a review that sums up more thoughtfully and eloquently how I felt about Post Office.

Tuesday, October 18, 2011

Book 32 - Far from the Madding Crowd

by Thomas Hardy

"This novel digs deep into the rhythms of rural existence. Hardy is unsurpassed when it comes to a sense of place and rich unsentimental evocations of landscape and local culture within which the characters find their fates."

–Charles Frazier

A few months ago, I watched the 2010 film, Tamara Drewe, which was likable enough, but more importantly, it got me to read the Thomas Hardy novel that the original comic drew inspiration from. And I’m so glad I finally did. I knew that this was arguably Hardy’s “happiest” novel, having only read Jude the Obscure, which, though beautifully tragic, was also a bit of a weepfest. Anyway, Far From the Madding Crowd was a wonderful read, it being easily another favourite of the year.

I very recently came across the Charles Frazier quote on Goodreads when he listed his favourite novels “with rural settings”. Though I agree with Frazier wholeheartedly, the quote makes it seem like character is secondary to setting or theme in this novel, which is far from the case. Hardy’s character studies are just as solid as his “rich and unsentimental” evocation of landscape. It's the depth of characterization and the strong pull of narrative that keeps 19th-century literature alive today, according to Jeffrey Eugenides (very curious abou his new novel The Marriage Plot). The fact that Hardy's story is basically a love quadrangle amidst a pastoral setting does not give it credit either. Within this quadrangle (at one point, it even becomes a love pentangle!), Hardy explores every aspect of love in all its human drama: the rituals of courtship, societal versus individual expectations and desires, infatuation versus love, the pains of unrequited love, and so much more.

The person that undergoes all this drama and transformation is the protagonist Bathsheba Everdene: a handsome, independent young woman who has inherited a farm and is courted by three suitors in the course of the novel. (Interesting piece of trivia: Suzanne Collins named her Hunger Games heroine Katniss Everdeen in homage to Hardy’s Bathsheba). The first suitor to court our heroine is Gabriel Oak, a shepherd of solid character but little money to his name; then it's William Boldwood, a respectable yet introverted gentleman in the neighbouring farm whose passion is set alight when he receives an innocent valentine from Bathsheba; and finally there is the dashing Francis Troy, a sergeant who has a way with the ladies, if you know what my mean. Bathsheba ends up falling for the wrong guy, tragedy ensues, but after learning from her mistakes, she ends up marrying the right guy in the end (well, kind of by default since by then, one suitor ends up dead and the other imprisoned for life!).

Through it all, Hardy explores what makes a bad romantic relationship and what makes a solid and healthy long-term relationship (known as a marriage back in those days). I have not read many 19th century novels, but this was also the first time I’ve come across a study in obsessive love, or “pathetic evidences of a mind crazed with care and love”, that was not set in a contemporary period. A lot of stuff gets explored in this novel. Hardy des a wonderful job in letting you inhabit the characters and understand how their actions impact each other’s behaviour. Like this one particular passage about Bathsheba’s unwitting influence on Farmer Boldwood:

The phases of Boldwood's life were ordinary enough, but his was not an ordinary nature. That stillness, which struck casual observers more than anything else in his character and habit, and seemed so precisely like the rest of inanition, may have been the perfect balance of enormous antagonistic forces--positives and negatives in fine adjustment. His equilibrium disturbed, he was in extremity at once. If an emotion possessed him at all, it ruled him; a feeling not mastering him was entirely latent...

Bathsheba was far from dreaming that the dark and silent shape upon which she had so carelessly thrown a seed was a hotbed of tropic intensity. Had she known Boldwood's moods, her blame would have been fearful, and the stain upon her heart ineradicable. Moreover, had she known her present power for good or evil over this man, she would have trembled at her responsibility. Luckily for her present, unluckily for her future tranquillity, her understanding had not yet told her what Boldwood was. Nobody knew entirely; for though it was possible to form guesses concerning his wild capabilities from old floodmarks faintly visible, he had never been seen at the high tides which caused them.

I also really admired Hardy for creating such an interesting female character in Bathsheba Everdene. As described in the Wiki, FFTMC “might also be described as an early piece of feminist literature, since it features an independent woman with the courage to defy convention by running a farm herself. Although Bathsheba's passionate nature leads her into serious errors of judgment, Hardy endows her with sufficient resilience, intelligence, and good luck to overcome her youthful folly.”

Feminist or no, there are times, however, when Hardy goes a little overboard with Bathsheba’s very “female” attributes and flaws, but ultimately Bathsheba is a remarkable character who is “indispensable to high generation, hated at tea parties, feared in shops, and loved at crises”.

Lastly, it is Hardy’s evocation of landscape that is also memorable. If anyone has ever seen paintings by Romantic landscape artist JMW Turner or French Realist painter Jean-Francois Millet, one could see that Hardy’s pastoral prose is a happy combination of romanticism and realism:

To persons standing alone on a hill during a clear midnight such as this, the roll of the world eastward is almost a palpable movement. The sensation may be caused by the panoramic glide of the stars past earthly objects, which is perceptible in a few minutes of stillness, or by the better outlook upon space that a hill affords, or by the wind, or by the solitude; but whatever be its origin the impression of riding along is vivid and abiding. The poetry of motion is a phrase much in use, and to enjoy the epic form of that gratification it is necessary to stand on a hill at a small hours of the night, and, having first expanded with a sense of difference from the mass of civilized mankind, who are dreamwrapt and disregardful of all such proceedings at this time, long and quietly watch your stately progress through the stars. After such a nocturnal reconnoiter it is hard to get back to earth, and to believe that the consciousness of such majestic speeding is derived from a tiny human figure.

One significant blight on my reading experience was not in the narrative itself, but in how the used trade paperback I had was bound. I only realized upon reaching page 289 that the next page was 320, so it was missing thirty pages! Luckily Hardy’s work is available from the Gutenberg Library and I was able to read the missing pages on my iPad. But as soon as I got to the first sentence on p. 321, I switched back to paper.

And get this. When I reached p. 352, the next page was 321 and it kept going until it got to p. 352 and from there I was able to read the novel to the end. But how fucked up was that? I had missing AND repeating pages in a single book. Never experienced such a thing before. Sadly I could not find the cover for this sorry excuse of a paperback online, but it kind of looked like the one pictured here. So I’m thinking it’s probably best that I throw this book into the recycling bin.

"This novel digs deep into the rhythms of rural existence. Hardy is unsurpassed when it comes to a sense of place and rich unsentimental evocations of landscape and local culture within which the characters find their fates."

–Charles Frazier

A few months ago, I watched the 2010 film, Tamara Drewe, which was likable enough, but more importantly, it got me to read the Thomas Hardy novel that the original comic drew inspiration from. And I’m so glad I finally did. I knew that this was arguably Hardy’s “happiest” novel, having only read Jude the Obscure, which, though beautifully tragic, was also a bit of a weepfest. Anyway, Far From the Madding Crowd was a wonderful read, it being easily another favourite of the year.

I very recently came across the Charles Frazier quote on Goodreads when he listed his favourite novels “with rural settings”. Though I agree with Frazier wholeheartedly, the quote makes it seem like character is secondary to setting or theme in this novel, which is far from the case. Hardy’s character studies are just as solid as his “rich and unsentimental” evocation of landscape. It's the depth of characterization and the strong pull of narrative that keeps 19th-century literature alive today, according to Jeffrey Eugenides (very curious abou his new novel The Marriage Plot). The fact that Hardy's story is basically a love quadrangle amidst a pastoral setting does not give it credit either. Within this quadrangle (at one point, it even becomes a love pentangle!), Hardy explores every aspect of love in all its human drama: the rituals of courtship, societal versus individual expectations and desires, infatuation versus love, the pains of unrequited love, and so much more.

The person that undergoes all this drama and transformation is the protagonist Bathsheba Everdene: a handsome, independent young woman who has inherited a farm and is courted by three suitors in the course of the novel. (Interesting piece of trivia: Suzanne Collins named her Hunger Games heroine Katniss Everdeen in homage to Hardy’s Bathsheba). The first suitor to court our heroine is Gabriel Oak, a shepherd of solid character but little money to his name; then it's William Boldwood, a respectable yet introverted gentleman in the neighbouring farm whose passion is set alight when he receives an innocent valentine from Bathsheba; and finally there is the dashing Francis Troy, a sergeant who has a way with the ladies, if you know what my mean. Bathsheba ends up falling for the wrong guy, tragedy ensues, but after learning from her mistakes, she ends up marrying the right guy in the end (well, kind of by default since by then, one suitor ends up dead and the other imprisoned for life!).

Through it all, Hardy explores what makes a bad romantic relationship and what makes a solid and healthy long-term relationship (known as a marriage back in those days). I have not read many 19th century novels, but this was also the first time I’ve come across a study in obsessive love, or “pathetic evidences of a mind crazed with care and love”, that was not set in a contemporary period. A lot of stuff gets explored in this novel. Hardy des a wonderful job in letting you inhabit the characters and understand how their actions impact each other’s behaviour. Like this one particular passage about Bathsheba’s unwitting influence on Farmer Boldwood:

The phases of Boldwood's life were ordinary enough, but his was not an ordinary nature. That stillness, which struck casual observers more than anything else in his character and habit, and seemed so precisely like the rest of inanition, may have been the perfect balance of enormous antagonistic forces--positives and negatives in fine adjustment. His equilibrium disturbed, he was in extremity at once. If an emotion possessed him at all, it ruled him; a feeling not mastering him was entirely latent...

Bathsheba was far from dreaming that the dark and silent shape upon which she had so carelessly thrown a seed was a hotbed of tropic intensity. Had she known Boldwood's moods, her blame would have been fearful, and the stain upon her heart ineradicable. Moreover, had she known her present power for good or evil over this man, she would have trembled at her responsibility. Luckily for her present, unluckily for her future tranquillity, her understanding had not yet told her what Boldwood was. Nobody knew entirely; for though it was possible to form guesses concerning his wild capabilities from old floodmarks faintly visible, he had never been seen at the high tides which caused them.

I also really admired Hardy for creating such an interesting female character in Bathsheba Everdene. As described in the Wiki, FFTMC “might also be described as an early piece of feminist literature, since it features an independent woman with the courage to defy convention by running a farm herself. Although Bathsheba's passionate nature leads her into serious errors of judgment, Hardy endows her with sufficient resilience, intelligence, and good luck to overcome her youthful folly.”

Feminist or no, there are times, however, when Hardy goes a little overboard with Bathsheba’s very “female” attributes and flaws, but ultimately Bathsheba is a remarkable character who is “indispensable to high generation, hated at tea parties, feared in shops, and loved at crises”.

Lastly, it is Hardy’s evocation of landscape that is also memorable. If anyone has ever seen paintings by Romantic landscape artist JMW Turner or French Realist painter Jean-Francois Millet, one could see that Hardy’s pastoral prose is a happy combination of romanticism and realism: